Notes for: You Don’t Know JS book series

[!info] title: You Don’t Know JS author: Kyle Simpson published: 2015 edition: 1 ISBN: 978-9352136261

Introduction

My notes from You Don’t Know JS (YDKJS) book series. Words from the author:

[!quote] It is simultaneously a simple, easy-to-use language that has broad appeal, and a complex and nuanced collection of language mechanics which without careful study will elude true understanding even for the most seasoned of JavaScript developers … Because JavaScript can be used without understanding, the understanding of the language is often never attained.

I will only be highlighting key attributes of JS that tends to be forgotten in our day-to-day work as engineers.

Compiler Theory

- In a traditional language compiler, the compilation process consists of 3 steps

- tokenizing/lexing: breaking up a string of characters in our source code into tokens.

- parsing: taking a stream of tokens and turning it into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST, a tree of nested elements representing the grammatical structure of the program)

- code-generation: process AST into executable machine/platform code

- compilers will typically perform optimisations during the 3-step process, to reduce memory/CPU/GC usage of the program when possible.

- JavaScript engines perform compilation right before code execution

- which is why it is typically classified as dynamic or interpreted language, but the 3-step process do happen.

- JS engines doesn’t have the luxury to perform a lot of code optimisation ahead of time, and it also needs to apply techniques to speed up compilation

- a basic understanding of how the compiler works, allows us to write better code, that avoids dynamic behaviour that prevents compiler optimisation/requires more runtime effort by the engine.

Scopes

a Variable in a Function Scope

Most of the time, there are only 2 scopes we are interested in: the Global Scope and the Function Scope.

When a variable is declared and assigned var test = 1, the following sequence will happen when code is run:

- Compiler will parse code into tokens

- Compiler will check if variable was already declared in Scope. If not it will request for variable to be declared in Scope.

- Execution Engine runs compiled code, retrieve variable from Scope.

- Variable retrieved and assigned value by Engine.

- If variable cannot be resolved in current Scope, the Engine will query from outer Scopes, searching up all the way until Global Scope if the variable cannot be found. a. by default, the variable will get created in Global Scope if deemed missing. b. in strict-mode, a ReferenceError will be thrown.

Shadowing refers to having the same variable identifier in the inner scope and outer scope. Since look up always start from the innermost scope, the shadow variable will be resolved instead of the outer scope variable. In most cases, this is our expectation from the Engine. Look up stops once a matching variable is found in the Scope.

In browsers, all variables declared in Global Scope are automatically properties of the Global Object “window” and are therefore accessible from any nested scope through accessing the Global object.

How are Scopes determined

YDKJS, Scopes & Closures, Chapter 2

[!tip] No matter where a function is invoked from, or even how it is invoked, its lexical scope is only defined by where the function was declared.

Lexical Scopes can be modified at runtime by eval, with, and some other built-in functions (strongly discouraged), which are restricted by strict-mode (Great!). Besides the danger of code injection through eval, performance of code will slow down. Scope will be dynamically generated when Engine executes the code, wasting all the optimization efforts of the Compiler from analyzing the static code before execution.

In short, we can assume JavaScript do not have Dynamic Scope (scope determined by where function was called at runtime in the call stack, instead of function declaration and respecting the lexical scope chain)

Another important concept:

[!tip] It is true that internally, scope is kind of like an object with properties for each of the available identifiers. But the scope “object” is not accessible to JavaScript code. It’s an inner part of the Engine’s implementation.

Namespace

- Instead of loading variables into your Global Scope, which may result in variable name collision

- the classic pattern is to use an object as a “namespace”, to limit the scope of imported variables, and to access them via object accessors.

- Modern approach is to use module dependency managers to achieve the same goal.

Block Scopes

Consists of:

- try-catch

- for loops

- { … }

Most of the time we may have allowed our functions to have closure over unnecessary data that are not relevant. Allowing those variables and data to be in block scope will limit exposure, and allow garbage collection once execution has passed that block.

let and const are block scoped declarations. Functions are not block scoped, so declaring it in the block will be hoisted to the enclosing outer scope.

Let vs Var vs Const

let

letis scoped to the immediately enclosing block,varis scoped to the immediately enclosing function.letis not hoisted, and will only be defined when that line of code is evaluated.- When used at top-level,

letwill not create a property on Global object. letdo not allow redeclaration of the variable within the same scope.

const

constis Block Scoped.- No hoisting.

- Will not create Global object property.

- No redeclaration. Must assign value on declaration.

special note on var

Calling var at the top level creates a property on the Global object. It is not a copy of the variable. It is the exact same variable.

Hoisting

Allows variable (var, functions) declaration anywhere in the lexical scope. When code is parsed by Compiler, the variables will be hoisted to the top and declared before execution starts in the scope, so that all declared variables are available.

Only declarations will be hoisted. Assignments will be left in place. Therefore, this snippet will print undefined despite hoisting.

console.log(test); // undefined

var test = 1;

hello(); // TypeError

my(); // ReferenceError

var hello = function my() {

console.log("my world");

};

foo(); // prints bar

function foo() {

console.log("bar");

}

Functions are hoisted before variables. If there are duplicated definitions of the same function, the last declaration wins.

IIFE - Immediately Invoked Function Expression

Typically used to create a scope for variables, isolated from the outer scope.

Function Parameter Scope Bubble

Parameters of a function are in their own parameter scope, with no access to function body scope.

Closure

YDKJS, Scopes & Closures, Chapter 5

[!tip] Closure is when a function is able to remember and access its lexical scope even when that function is executing outside its lexical scope.

We use “closure” as a verb, with meaning close to “reference”. A function has “closure” over certain internal variables/scope. The internal variables are akin to internal state of an object. Start state can be injected on creation.

function multiplyByX(x) {

function multiply(input) {

// multiply function has closure over scope of enclosing function.

return input * x;

}

return multiply;

}

var multiplyByFive = multplyByX(5);

// function is executed outside of its declared lexical scope of multiply, but still retains access to the scope

console.log(multiplyByFive(5)); // 25

Testing our understanding of how javascript works: loops + closure, example from the book

for (var i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

setTimeout(function timer() {

console.log(i);

}, i * 1000);

}

// prints out the number "6" every second.

What is happening? In my own understanding:

- for-loop body only has one scope, regardless of the number of iterations

- variable i is bound to a new iteration value at every loop

- at every loop, we will set timeout, with a function called timer, with a closure over the scope of the for-loop (therefore only one single scope, ever)

- after the loop has ended, when each callback gets executed, the closure will reference variable i from for-loop scope, which already has value set to 6 (since the loop ended)

- this behaviour is consistent even if timeout value is set to zero.

To make the loop work as intended, we need to freeze the value of the variable within our timeout function scope or timer function scope, and have a new scope instance on each iteration, instead of having a closure of the changing for-loop scope. The author used an IIFE to create a scope per iteration. But I think my example using block scope is easier for us to appreciate the concept.

for (var i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

const k = i; // constant k is block scoped, and assigned on declaration at each iteration.

setTimeout(function timer() {

console.log(`block scoped ${k}, for-loop scoped ${i}`);

}, k * 1000);

}

for (let i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

// or more simply using block scoped behavior of let.

setTimeout(function timer() {

console.log(i);

}, i * 1000);

}

Implementing Module Pattern

The module pattern can be implemented with closures to satisfy these conditions:

- There must be an outer enclosing function, and it must be invoked at least once to create a new module instance.

- Enclosing function must return an inner function with closure over private scope of enclosing function.

What is THIS?

THIS is a binding in the execution context, not the SELF, not the SCOPE

this is a context object available to the function scope during execution.

When a function is invoked, an execution context is created. The execution context contains various information:

- where the function was called from (the call-stack)

- how the function was invoked

- what parameters were passed

- the

thisreference, which will be determined by call-site (how the function was called)

(inspecting from the devTool will allow us to see the execution context, and also the scope chain)

Rules that determines THIS binding

Default Binding

- With no modifiers, the default binding of

thisis to the Global object. - Strict mode do not allow default binding, so it will be

undefined.

Implicit Binding

If a context object references the function as part of the object property, e.g. obj.func(), then this context object obj will be bound to this and be available to the function func.

Therefore, it is critical that a context object is used to invoke the function, if it is just a reference assignment of the function through an object, the implicit binding will be lost. This is especially common for callback functions. (e.g. React components passing callback functions to Child components).

function sayHello() {

console.log(this.hello);

}

var obj = {

hello: "Ni Hao!",

sayHello: sayHello,

};

var justAReference = obj.sayHello;

justAReference(); // default binding!

[!warning] Event handlers in popular JavaScript libraries are quite fond of forcing your callback to have a

thiswhich points to, for instance, the DOM element that triggered the event

Explicit Binding

Make use of JS Function Utilities, the call and apply methods of Function objects allow explicit binding by passing the desired context object as method parameter.

If a primitive is passed as context object, they will be boxed to become the object from through object wrappers.

These utilities allow dynamic binding of this through explicit reference.

The bind method provided in ES5 and ES6 an object to a function, and returns a reference to a new function that is hard bound to the object.

ES6 adds a name property to the resultant function, that indicate the name of the source function before binding.

Many libraries provide functions with optional context parameters, giving us the convenience to explicitly bind an object to this as we make our function calls.

NEW Binding

In JavaScript, there is no Java equivalent of a constructor function.

All functions are just… functions.

A new keyword merely modify the invocation and return object of that function in the following sequence:

- a new object is created

- the newly created object gets prototype-linked to that function’s prototype object

- the newly created object gets bound to

thisof that function call - function gets executed

- unless the function returns its own alternate object, the newly created object will be returned by default

- I think of this sequence as a decorator around the function.

- And unless the new object is required by this constructor call, if not the

newkeyword can be omitted and the function should still behave as expected as a constructor call, it all depends on how you have coded the function. - Omitting the

newkeyword if it is redundant will avoid additional object creation and garbage collection.

Remember, there is no constructor in JavaScript.

Binding Priority

- Explicit Binding takes precedence over all other bindings (if used in conjunction).

- However,

newBinding is able to override hard boundthisin a function, making the function apply on the new object and return the new object instead. This allows possibility of partial application (subset of currying). - Implicit Binding takes precedence over Default Binding.

- Rules fall through to Default Binding.

new > explicit > implicit > default

Note: you cannot bind to an explicitly bound function again to override the context.

ignoring THIS

- Calls to explicit binding may be used for other purposes, such as spreading arguments or currying.

- However, the binding context is a mandatory parameter.

- If we pass in

nullorundefinedfor binding, we will fall back to Default Binding on Global object, which may cause unintended modifications on the Global object by other callers of the function. - An empty object

Object.create(null)can be passed instead as a safethisbinding. This object is more efficient than an object created by{ }expression, since there is no delegation fromObject.prototype.

Soft binding is:

- not using default binding (

globalor `undefined), but instead use a custom binding as a fallback - however, the function user still has flexibility to manually bound

thisto their own context using implicit/explicit binding

The author suggested using a helper soft-bind function to emulate a desired soft binding behaviour.

lexical THIS in arrow functions

- An arrow function do not bind

thisaccording to the above binding rules, but instead inheritthisfrom the lexical scope of the enclosing function. - In simple terms, the lexical scope determines what

thiswill be inherited by the arrow functions, instead of the call-site of the function (but of course, the binding rules still apply to the enclosing function). - the author encourage using either a pure lexical scoping style of coding, or a pure context binding style of coding, instead of mixing both concept, which may make our code hard to maintain (I think this is especially true in a team environment).

Objects

Not everything in JavaScript is an Object.

- Primitives are not objects. They will be coerced or boxed into objects when you use object operations on them.

- Object subtypes can be called complex primitives. These are functions and arrays.

- All object access are property access.

- The objects do not truly “own” a method in the traditional Object-Oriented language sense, just because the function is referenced by one of the object property.

- Even if the function access other object properties through

thisreference, this is determined by context binding during invocation.

Shallow Copy

Since objects can contain properties that are infinitely nested objects or contain circular references, ES6 provides Object.assign(newObject, sourceObjects... ) that creates a shallow copy only.

If an object is JSON safe, then JSON.stringify followed by JSON.parse on the string will create a new distinct object with no shared references.

Data Descriptors

A property of an object that describes data. Such a property can be configured using Object.defineProperty(obj, property, config). The configurations available:

- Value - value/data of the property

- Writable - determines if value of property can be changed.

- Configurable - determines if property descriptor can be updated. (one-way action once set to false). Also determines if a property can be

delete. - Enumerable - determines if property will show up during enumeration over all properties of object using

for..in.

Array should be enumerated using for-loop that act on indices only, instead of using for..in to prevent accessing other enumerable properties of Array object. ES5 offers useful helpers to iterate over Array values instead, but with no guarantee on ordering of Array elements

Enumerable and Iteration

- ES6 provides

for..ofloop, which requests for the object’s iteratorSymbol.iteratorproperty to iterate through the property values. - This iterator is built-in for Array subtypes therefore we can use

for..offor arrays immediately, but will need to be provisioned manually for other object types. - Compared to

forEachwhich takes a callback to apply to each element of the array,for..ofallows early termination but requiresSymbol.iteratorproperty.

Object-level configurations

Object.preventExtensions(obj)prevents new property from being added to the object.Object.seal(obj)makes object non-extensible, and make all existing properties non-configurable.Object.freeze(obj)seals the object, and make all existing properties non-writable.

Accessor Descriptors

- If an object property is defined with getter or setter functions, it is considered an accessor descriptor.

- JS will call the getter or setter to access the data, and the value and writable configuration of the property will be ignored.

- Getters and Setters can be defined at a per property level, overriding default function behaviour.

- So if the property remains as a data descriptor, the default

[[Get]]and[[Put]]function will be used to access the value. These are the functions that gets overridden when the property upgrades to become an accessor descriptor.

Missing Property

- Accessing a missing property will return

undefinedunlike referencing a missing variable which throws ReferenceError. - If a property exists, but was set to value

undefined, there is another way to test of existence of a property instead of testing the value of a property, by using the following:obj.hasOwnProperty(property)checks if this particular object has property.property in objchecks if this particular object, or the prototype chain, has the property.

- There is no built-in way to list all properties of an object including properties up the prototype chain.

Object.keys(obj)will list all properties of the current object that are enumerable.Object.getOwnPropertyNames(obj)will list all properties of current object regardless of enumerability.

Classes

Classes in the traditional Object-Oriented sense do not exist in JavaScript.

Inheritance via Mixin

- Since classes do not exist in the language, all “class” definitions are merely objects.

- Inheriting a parent “class” to a child “class” can be emulated by performing a shallow copy of all the parent object properties if they don’t exist in the target child object

- Methods can be extended/overridden using explicit pseudo-polymorphic reference.

- But even this does not provide true OOP inheritance that creates a new copy of the behaviour, as the parent and child now shares reference to a common function.

This is a common and traditional approach, called Explicit Mixin.

// invented function mixin

function mixin(sourceObj, targetObj) {

for (var key in sourceObj) {

targetObj[key] = sourceObj[key];

}

return targetObj;

}

var Child = mixin(Parent, {

myFunc: function () {

Parent.myFunc.call(this); // explicit reference to Parent object, due to shadowing of method name

console.log("Extended functionality");

},

});

Parasitic Inheritance is a variant of the above explicit mixin, by creating a parent object reference within the child object and maintaining privileged references to whatever properties the child would like to inherit.

function Child = {

var child = new Parent() // parent object reference

var parentMyFunc = child.myFunc // privileged reference

function myFunc() {

parentMyFunc.call(this);

console.log( "Extended functionality" );

}

return child

}

Implicit Mixin is another approach to mixin, which make use of context binding to borrow behavior from a parent “class” and applying it to a child context object, hence inheriting the behavior.

Prototype

- JavaScript objects typically has an internal property denoted as

[[Prototype]]which is a reference/link to another object. - When trying to access a property on an object, but the property does not exist in the current object, the prototype chain will be consulted to look up the chained object for the property.

- Once the property matches, it will be returned.

- The look-up stops once it reaches the root of the chain, with is the JavaScript

Object.prototype. var newObj = Object.create(srcObj)creates a new object by settingsrcObjas the prototype reference.

Setting Properties in Objects

Setting properties in object using assignment (obj.property = value), especially if the property do not exist in the current object, is not straightforward.

- if property exists in prototype chain as a data descriptor, and if it is writable, then a new shadow property will be created on current object.

- if property exists in prototype chain as a data descriptor, but is not writable, then nothing will happen. In strict mode, it will throw an error.

- if property exists in prototype chain as an accessor descriptor, then that accessor will be called to set the property value. The value will be set in the object higher up the prototype chain, instead of having a shadow property.

- if property is set using

Object.defineProperty()instead, a new (shadow) property will be created on the current object.

Prototypal Delegation

Prototypal delegation should be the defining mental model to understanding JavaScript objects.

[!tip] Objects do not inherit behaviors. Objects delegate behaviors that are missing from their own properties to a prototype chain. The prototype chain is essentially layers of behavior, and you resolve what an object can perform by flattening the layers of behavior into a projection. In short, an object never truly “owns” a majority of behavior it can perform.

Confusing Constructor

- An unfortunate naming that cause confusion is the property

prototype.constructoron a function. - Functions are created by default with a prototype link to an arbitrary object. That arbitrary object contains a property called

constructorthat reference back to the function. - In other words, it is easier to think of

prototypeandconstructorin this case as doubly linked references (like a doubly linked list) at the point of function creation. - The word

constructorreally does not carry any additional meaning, therefore it never indicates what is the constructor of an object. That is pure misconception. - So when a new object is created by a function through a

newconstructor call, trying to access thatnewObj.constructorproperty will search up the prototype chain to resolve a value, that creates an illusion of what is the constructor. (In complex scenario with shadow properties, you may even resolve to an unexpected value).

Setting the Prototype

Child.prototype = Parent.prototype; // bad. shared prototype may cause corrupted modifications

Child.prototype = new Parent(); // bad. constructor calls to Parent() may cause undesired side effects

Child.prototype = Object.create(Parent.prototype); // pre-ES6. Wasteful discarding of original arbitrary Child.prototype object

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child.prototype, Parent.prototype); // ES6. Reuses Child.prototype object.

The conceptual model in my mind is to wrap prototype links with a Prototype Object. This object itself allows future “grandchildren” objects to delegate behaviors, yet keeping these behaviors isolated from parent prototype objects:

Child = {

privateChildProperties,

prototype: {

// child's Prototype Object

extraChildBehaviors,

prototype: parent.prototype, // references parent's Prototype Object

},

};

Parent = {

privateParentProperties,

prototype: {

// parent's Prototype Object

extraParentBehaviors,

prototype: grandparent.prototype,

},

};

Object.getPrototypeOf() and Object.setPrototypeOf() should be used to interact with prototype objects, although legacy approach like .prototype and .__proto__ will work as well.

Finding prototype chain ancestor

child instanceof Parent

- This call checks if

child’s prototype chain ever contained the prototype object of theParentfunction. - If Parent is a hard-bound function (it will not have a prototype property), the original function before binding will be consulted.

parentPrototype.isPrototypeOf(child)

- This call is better, as it avoids having a function involved in this testing, and only requires two objects for comparison.

Coding

Strict Mode

- Complying to strict mode makes code more optimisable for the compiler

- Therefore, there is no reason not to use it.

Why Named Function is preferred over Anonymous Function

Anonymous functions makes code more readable but has the following drawbacks:

- No useful names will be displayed during stack trace or debugging

- Cannot use recursion, or allow the function to unbind itself as an event handler

- Cannot self document or carry intentions

- However, the Arrow functions are anonymous functions that introduces the lexical

thisbehaviour, and we still need to use it if we adopt lexical-scope style.

Delegation Design

Achieving object-oriented programming with delegation instead of class inheritance, here are some points to keep in mind:

- Delegate behavior to another object via prototype linkage. But keep states internal to current object. (I find this the most profound concept to wrap by head around).

- Use explicit method naming on delegator objects, instead of shadowing a method with the same name from the delegates.

- This makes code simple to maintain and reason.

- Polymorphism can be achieved by having the same method name between sibling delegators that are not on the same prototype chain.

- Delegation should be hidden as internal implementation of an API, if it provides more clarity to users.

- Bidirectional delegation is not allowed.

- Using composition of peer objects providing distinct behaviour, instead of always designing the objects in terms of parent-child hierarchy.

- Use

obj.isPrototypeOf()andobj.getPrototypeOfto test for delegation, and forget all about classes andinstanceof.

Class Approach

If we are using class in our development work, then I think the best practice is to never use any Delegation Design explicitly.

Even though class from ES6 may be using prototypal delegation under the hood, we should respect the class API and stick to creating static and traditional OOP classes. I see two advantages:

- we are using the new class inheritance syntax as intended by ES6 specs.

- we do not cause unintended corruption to our program by accessing prototype delegation.

- if a problem cannot be solved using class features, then defer to a higher level workaround, such as changing design pattern, to approach the problem, instead of hacking it by using other JavaScript language features.

ES6 Class

classkeyword creates a function by defining the function prototype in a block.constructordefines the signature of a function with the same name as theclass.- Class methods are non-enumerable by default.

- Calling the class function must be made with

newkeyword. - Class definitions will not be hoisted, therefore they must be defined before usage.

- Class definitions do not create a Global Object property.

- Class can be perceived as a macro to automatically populate prototype.

EXTENDS and SUPER

class Child extend Parentessentially establish a prototype delegation link from a “child” class prototype to “parent” class prototype.- Calling

superin the child constructor method is synonymous to calling theParent()constructor method. - Calling

superin any child class method is synonymous to callingParent.prototype. superis therefore not limited to “classes”, and can be used for object literals.extendssimilarly allows us to extend native types.- Most Importantly, SUPER is statically bound at declaration, and not dynamically bound, like THIS.

- The default subclass constructor, if not defined, will actually call the parent constructor via

super(args). - In ES6,

thiscannot be accessed by subclass constructor, untilsuper()is called, as the context of an instance is initialised by the parent constructor.

STATIC

- Besides linking between subclass prototype and parent class prototype, the child function object is also prototype linked to the parent function object

- This of it as two separate and parallel prototype chains, one chain for the class instance and one chain for the class.

staticmethods declared by the parent class will not be added to function prototype, but is still available to child class through the above-mentioned function object prototype chain.

ES6 Function Definition Shorthand

var Example = {

anon() {

/*..*/

},

named: function named() {

/*..*/

},

};

- This example uses of simpler syntactic shorthand to create a function to be used in constructor call

- the concise method

anon()will create an anonymous function, which may limit the ability to self-reference in the function code.

Variable Existence Check

if (variable) {

// ... do something to variable

}

- If the variable does not exist (not declared) this will definitely throw an error.

- A common way to test this is to use

typeof var !== "undefined"instead. - This is a legacy feature, where even though the variable was not declared and cannot be referenced without throwing error, we can still safely check for existence using

typeof. - Reason being, some legacy libraries imported in older JS environment pollute the global namespace with variables, and we need a method to check for existence of those imported variables safely.

- This does not apply to variables stuck in Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ).

- TDZ begins at the start of a block scope, and ends when the variable is declared.

- During TDZ, trying to access the variable will lead to ReferenceError

{

typeof variable; // ReferenceError

let variable;

}

Built-in Types

string, number, boolean, null, undefined, object, symbol

typeof null is “object”

- This is a bug that will never be fixed, since many websites around the world depends on this behaviour.

- Fixing this will break a lot of websites.

typeof functions and arrays

- functions and arrays are just special variants of objects with certain built-in properties. We can consider them subtypes.

- However, typeof functions will state “function”, but for array it will state “object”.

Safe Numbers

0.1 + 0.2 === 0.3is false, as with most programming language’s implementation of floating point number.- A workaround for this is to determine that the two numbers are close enough to be equal, using the built-in tolerance range

Number.EPSILON.- e.g.

0.3 - (0.1 + 0.2) < Number.EPSILON

- e.g.

- Besides decimal numbers, integers that are either too big are too small will also have safety problem.

- The predefined safe range can be accessed using

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGERandNumber.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER.

- The predefined safe range can be accessed using

- Bitwise operation can only be performed on 32-bit integers. Using an operation like

largeNumber | 0will return a 32-bit integer since other bits will be ignored.

Special Values

undefinedandnullare both a type and a value.voidcan be used to void out any return value from an expression, ensure that it always returnsundefinedNaNa.k.a not-a-number is a special number indicating that the value is invalid.- It is usually the result of a numerical operation performed on other non-number types.

- A

NaNcan never equal any value, not even itself, and it is the only value with such behaviour in the language.

var notNumber = Nan;

notNumber !== notNumber; // true!

- To safely test for

NaN, useNumber.isNaN().isNaNdoes not check for the value, it merely checks if something is anumberor not

Infinityand-Infinitycan be obtained when dividing a number by zero, or by accessing the valueNumber.POSITIVE_INFINITYandNumber.NEGATIVE_INFINITY.- By specification, if any operation causes the number to go beyond

Number.MAX_VALUE, it will not automatically return infinity, but will actually go through a rounding process to determine if the number is closer to the MAX_VALUE or to infinity, so it may return MAX_VALUE instead. 0is positive zero, and-0is the result of obtaining zero from division or multiplication involving negative numbers.- Comparison operation between positive and negative zero will determine that they are equal, and even for some string operations, depending on browser support.

- The following snippet can be used to test for negative zero.

var negativeZero = -0

(negativeZero === 0) && 1 / negativeZero === -Infinity;

- Negative zero is a feature used to support preserving of the sign (direction) for certain operations that leads to zero value without losing that piece of information.

With ES6

Object.is(value, NaN);

Object.is(value, -0);

This utility was introduced to help test for special values easily.

Boxing

- Manually boxing will create object forms of primitives, using native wrappers.

- These object internally uses a

[[Class]]attribute to remember what type the value belongs to. - Unboxing can be performed manually using

.valueOf()function, or implicitly when coercion takes place.

Take note of the following pitfall.

var f = new Boolean(false);

if (!f) {

// will never run since object is truthy

}

var a = Array(3); // empty array, works without new keyword

a.length; // 3

var optimized = /^a*b+/g; // compiled

var unOptimized = new RegExp("^a*b+", "g"); // only useful to generate dynamic regex

var dateString = Date();

var dateObj = new Date();

var err = Error("message"); // works without new keyword

Coercion

- Number coercion for non-number types may contain pitfalls.

- Better double-check the coercion results before implementing it in your code.

parseInt()andparseFloat()only works on strings, so providing any other types will result in coercion to string, and the result may not be what we expect.+operator has specification to perform concatenation if operand are strings, so this is commonly used to coerce number to string.-operator however, only has specification for numbers, so strings will be coerced to number instead when used as operand. This applies to other arithmetic operations.- Objects are always coerced to their primitive value first

- and if the value does not meet the operator specifications, it will then fall back to other type coercions, like using

toString(). - If no rules can be matched, then it will throw a TypeError.

- and if the value does not meet the operator specifications, it will then fall back to other type coercions, like using

== vs ===

==double-equal allows coercion when comparing value===triple-equal does not allow coercion, also known as strict-equality- When compared with numbers, strings are coerced to

NaN(which is a number that don’t hold value) - Even though the author encourage the use of coercion equality as long as you follow certain heuristics to make sure it is safe, I beg to differ.

- In a team setting when collaborating on a project, it is better to be explicit than sorry.

- If you are implementing a functionality using equality, the next engineer that uses your function may not know about the implicit assumptions.

- Therefore, I advocate using strict-equality when possible

If coercion equality == is used, here are some quick tips according to specifications:

- Comparing number to string always coerce string to number, and it is commutative.

- Comparing anything to boolean, will coerce the boolean to a number.

- Comparing

nulltoundefinedalways yield true. Commutative. - Comparing Object to primitive will coerce the object first to primitive. Commutative.

- it seems that in no situation of comparison would result in values coerced to boolean, so we should resist the urge to think that way even if it is more intuitive.

For inequality, which cannot avoid coercion since there are no such option, the specification is:

- first coerce both operand to primitives

- if both are not strings, they will then to coerced to numbers

- the comparison will be performed using numbers

- if both are strings, then they will be compared lexicographically

For <= or >= inequality, the specification state that an ordinary < or > will first be performed then the result will be negated before returning.

Selector Operators && and ||

These are in fact selectors because they always return one of the operands.

||returns the first operand itself, if it coerces to boolean true, else it returns the second operand.&&returns the second operand if the first coerce to boolean true, else it returns the first operand.- they are actually equivalent to

first ? first : secondandfirst ? second : first ||can be used as a fallback operator to provide a default value (coalescing).&&can be used as a guard operator to only execute an operation if the first condition has been met.

These selectors are useful for defensive programming.

Falsy & Truthy

Values that are falsy when coerced to boolean value:

undefinednullfalse+0, -0, NaN""(empty string)

Notice that these are all primitives, therefore for most complex primitives, since they are not on the list, they are truthy by default, such as new Boolean( false ) is actually truthy.

Tilda~

- Tilda

~is a bitwise operation that flips all the bits and plus one. - Most commonly used to conveniently convert failure return values (-1) to falsy, because

~-1returns zero, but all other number values will not return zero. - Another use is to cast the number to 32-bit

~~variableby using the operator twice. This is more concise than performingvariable | 0due to operator precedence. - But usage of tilda is pretty rare, so unless the entire development team are familiar with it, or there is a strong case to use it, I would recommend avoiding it.

Symbols

Symbols create a unique scalar primitive on every invocation regardless of key provided:

Symbol("key") === Symbol("key"); // false

- If a symbol is used as property key in objects, it helps to prevent collision.

Object.hasOwnPropertySymbols(obj)provides a quick way to list all symbol properties in an object.- ES6 uses symbols for some prototype properties in Object and Array types.

Built-In Types Prototypes

An interesting behaviour for the following built-in prototypes which are all objects:

Function.prototypeis also an empty functionArray.prototypeis also an empty arrayRegExp.prototypeis also a regex that matches nothingString.prototypeis also an empty string

ES6 Maps and Sets

- Instead of using objects as maps, ES6 provides a new

Mapconstructor for creating map - This allows us to convey our intention through our code better

- It also allows non-string keys

- In addition, the Map API provides certain convenience method that allows us to retrieve an iterator for the stored values

- WeakMap is a variant of Map that only stores objects as keys.

- If the objects get garbage collected, the entry will also be removed from the map.

- Only the keys are held weakly, not the values.

- Sets also has a WeakSet variant that holds its values weakly. Note that values must be objects.

Pass by Value/Reference

- If you have been using JavaScript for a while, it should be clear how the language behaves without any explicit explanation, since it is quite intuitive.

- Whether a variable is passed by value or by reference purely depends on the type of value.

- And regardless of type, the variable will always be passed as a copy.

- Primitives are always passed by value.

- Complex primitives are always passed by reference.

- And unlike C, you cannot reference another reference (pointer to a pointer), therefore you cannot reassign an original reference by passing a complex primitive to a function, since the function always receives a copy of the reference, instead of the original reference itself.

- In simpler terms, if you pass a reference to an object to a function

- you can modify the object inside your function

- but you cannot make the reference point to an entirely different object, and expect the caller to see this change

- because the function received a copy of the reference, not the actual reference that the caller is holding

Array Shortcuts

array.length = 0is apparently the fastest way to achieve the clearing of an array in-place without reassigning reference. (Not sure why this works. To find out.)Array.of(...)creates a new array with given elements, even if it is only a single number, instead of allocating an empty array of size specified by that single number (behaviour of classic array constructor).Array.from(...)converts an array like object into an array, with an optional callback function we can specify as mapper.

Assignment Shortcuts

var a, b, c;

a = b = c = 3;

GOTO

This feature is not widely used. We can create labelled statements and use these labels in loops.

label: for (somthing) {

secondLabel: for (anotherCondition) {

// ... some logic

if (toContinueFromOuterLoop) {

continue label;

}

if (toBreakFromInnerLoop) {

break secondLabel;

}

}

}

- this example only seeks to demonstrate the behaviour of GOTO labels

- I would recommend following Golang best practice: only GOTO a label that is defined in a later/future step of execution, to avoid creating unpredictable/looping flows

Automatic Semicolon Insertion

- Is an error correction feature of JavaScript parser.

- Which means that semicolon is actually not optional, and that was never the intention of the language.

try-catch-finally

finallywill always be executed aftertrybut before the enclosing function finish executionfinallyis able to override any returns or throws from thetry/catchblocks, if explicitly returning/throwing from thefinallyblock.- if

finallyperforms a side effect, then bothtry/catchblock return values, and side effects will take place.

HOWEVER, these blocks are synchronous, so if any asynchronous callbacks are registered within any of the blocks, there is no guarantee for the execution order of those callbacks. In other words, try...catch an async promise will never work if you are trying to use it to catch async errors.

else-if

This actually a syntactic shorthand, and not an official language feature. It is equivalent to:

else {

if { }

}

Switch Hacks

A simple trick to overcome the default equality comparison of switch-cases.

switch (true) {

case variable === something:

break;

case variable === somethingElse:

break;

}

Spread and Gather

var arr = [x, ...y, z]; // var y will spread all its element

var a, b, c;

[a, b, ...c] = arr; // var c will gather all remaining elements.

function manyArgs(...args) {

args.shift(); // args is an array, all parameters are gathered

console.log(args);

}

Destructuring and Default values

- Destructuring allows us to set default values for variable assignments.

- This may create confusion when we try to perform destructuring, specifying default values for destructuring assignment, all within the definition of a function parameter, with default parameter value thrown into the mix.

Metaprogramming

Metaprogramming is used to let the program focus on itself or its runtime environment, to extend the normal mechanisms of the language to provide additional capabilities.

Proxycan be used to wrap an object and modify behavior or trigger additional handlers before invoking the actual object properties.ReflectAPI can be used to intercept and manipulate objects at runtime.

Async

Inversion of Control (IOC) of Callbacks

The callback pattern for asynchronous code inherently give control to another function to invoke your own callback. Often, this other function will be provided by third-party library, leading to several uncertainties:

- Will the callback be invoked at all?

- Will the callback be invoked more than once?

- Will the callback be invoked too early (turns out to be synchronous) or too late (after other critical events)?

- Will the calling function not pass along the necessary environment?

- Will the calling function suppress the error from the callback?

Instead of surrendering the control of your own program execution to a third-party function, Promise invert the control back to your program.

Promises

Promises = encapsulation of future values into a standardised and trustable API.

Temporal and Immutable

- Promises encapsulate temporal dependence and allow us to write code with predictable outcome.

- Promises are immutable, therefore they allow all parties to observe the same value, and prevents any party (e.g. IOC from calling third-party functions) from modifying the promise, which may corrupt the processing of others.

var p = Promise(...);

p.then( observerA );

p.then( observerB ); // observes the same event

Thenable Duck Typing

- Currently, the only way to determine a promise is through thenable duck typing.

- But since having a

thenproperty is not exclusive, and may conflict with certain legacy libraries from pre-ES6, this is a pitfall and may potentially cause problems. - A way out is to wrap those legacy functions or objects with a promise.

Trustable

Promise solves all the IOC callback issues by providing certain guarantees:

- Promises cannot be observed synchronously.

then(callback)is always asynchronous. - Promise observers do not delay or disrupt other observers from triggering their callbacks.

- Ordering within a promise-callback chain is guaranteed, but not across chains therefore we should never depend on such cross-chain patterns to enforce ordering.

Promise.racecan be used to set timeout on promise to prevent waiting indefinitely.- Even if the promise definition makes multiple calls to

resolveonly the first call will be registered. This guarantees that callbacks will be invoked only once. - Only the first parameter to

resolveandrejectwill be passed to the registered callback. - Additionally, callbacks can inherit environment from the closure over their scope, which can be used as a mechanism to pass variables even for promise-style programming.

- Most importantly, any non-promise but “thenable” functions can be wrapped with a promise, to give us guaranteed and consistent behaviour and API.

The promise of promises (pun intended) is to return a promise from each then(callback), which can be chained and our code will only need to work with the promise interface to enforce async behaviour.

Resolve and Reject

rejectsimply rejects the promise- but

resolvecan either fulfil the promise or reject it.resolvewill fulfil if passed an immediate, non-Promise, non-thenable value.- but if it is passed a genuine Promise or thenable value, that value is unwrapped recursively, until a final value is obtained, which may turn out to be promise rejection.

Rejectwill not recursively unwrap a promise or thenable value, so our code will need to explicitly callthenon the rejected value, if it turns out to be a promise.Promise.rejectandPromise.resolveare shorthands to bypass the creation ofnew Promise()objects.

Error Handling

Promise()

.then(callback)

.then(resolutionHandler, rejectionHandler)

.then(callback)

.catch(rejectionHandler);

- Error handling happens on a per-promise basis.

- If rejectionHandler returns a value, it will be wrapped in a promise and be propagated down the chain.

- By default, any unhandled error within a promise will cause a rejection, and if there are no rejection handler, the error will fall through the chain, and eventually bubbles up the program.

- The final

catchis actually just a shorthand for.then(null, rejectionHandler).- Therefore, if a synchronous error happens before a promise is even created (e.g. misuse of API), this rejection handler will not be able to catch it.

- Keep in mind that sometimes, it may be impossible to clean up reserved resources through rejection handlers, and promise mechanism lacks a

finallycapability to ensure clean up.

Built-in Patterns

Promise.all([...])returns an array of resolved values, or first rejection to occur.Promise.allSettled([...])likePromise.allbut waits for all promises to resolve/reject.Promise.race([...])returns only the first resolved value, or first rejection to occur. NOTE passing an empty array will cause you to wait indefinitely.Promise.any([...])is likePromise.allbut ignores rejection.

Generators

Generators are functions that can pause and resume their execution by yielding control to another function through an iterator as interface.

function* myGenerator(originalInput) {

var newInput = yield "hello";

var secondInput = yield "world";

return newInput + secondInput + originalInput;

}

var it = myGenerator(1); // only returns iterator. Generator code do not run.

var resultObj = it.next(); // starts generator code, pauses at first yield statement

resultObj.value; // "hello"

resultObj = it.next(2); // var newInput will store the value 2

resultObj.value; // "world"

resultObj = it.next(3); // var secondInput will store the value 3

resultObj.value; // returns 6 and the generator terminates.

- Generators can be created using

*syntax. - Each iterator controls an instance of the generator.

- An initial

nextcall is required to start the generator code running. - Generator will eventually run to completion, and result obtained by iterator will contain

done: trueflag. yieldandnextforms two-way message communication like a two-way latch gate.- A message sent by

nextwill be provided to the currentyieldand the value from the subsequentyieldwill be passed back instead.

- A message sent by

for (var val of it)will first retrieve an iterator from the object, before calling next on the iterator.- An iterator is itself an iterator and an iterable. (fetching the value of

[Symbol.iterator]on an iterator returns the iterator itself).

- An iterator is itself an iterator and an iterable. (fetching the value of

it.return(val)will terminate the generator (donewill be set to true), and this call to the iterator will create a result object with valueval.it.throw(err)will throw an error from the currentyieldin the generator.- Iteration can be delegated to another iterator through the

*syntax. Delegation will “step in” to the other iterator, and any message passing/error throwing betweenyieldandnextwill also be delegated.

function* myGenerator(originalInput) {

yield "hello world";

yield* anotherGenerator(); // iterator of an instance of anotherGenerator

yield* [1, 2, 3]; // will use iterator of this array

}

Generator-Promise Pattern (Async-Await)

[!tip] The natural way to get the most out of Promises and Generators is to

yielda Promise, and wire that Promise to control the generator’s iterator.

We can work with promises in a synchronous coding style by creating our workflow inside a generator.

- Whenever an asynchronous promise is created, we yield that promise.

- Outside the generator, a runner utility can be working with the iterator of this generator instance, and observe the yielded promise.

- The runner utility will register a callback to the promise, and pass the promise resolved value to the generator through

it.next. - Generator receives the value from

yieldand continue processing.

function* asyncGenerator() {

var data = yield asyncRequest(url);

var secondData = yield asyncRequest(url2);

}

function runnerUtility() {

var it = asyncGenerator();

var firstPromise = it.next();

firstPromise

.then((data) => {

return it.next(data);

})

.then((secondData) => {

return it.next(secondData);

});

}

But instead of having these cumbersome boilerplate, we can simply use async-await, which provides syntactic shorthand for this exact same pattern.

Projects

Polyfill

Producing a piece of code that is able to run in older JS environments, to emulate the behaviour of functions introduced in newer version JS that are not supported in current environment.

Transpile

Producing code with equivalent behaviour in older JS environments, for code written in newer version JS syntax.

ES6 Modules

Traditional Modules

- Traditionally modules are simple outer functions with inner variables and functions that we can access through object property.

- This is used by Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD) and Universal Module Definition (UMD).

RequireJSis a project that helps to load modules that implements AMD API, and primarily runs on browser.CommonJSis a project that helps to load modules for server-side JavaScript programs. Loading happens synchronously. (usesrequireandexportsobject).NodeJshas its own module system that is similar to CommonJS. (usesrequireandmodule.export).SystemJSis another module loader project that supports all the above systems, including ES6, and is configurable (essentially wraps all the systems with a common interface).

New Approach

ES6 has syntax support for Modules.

- Modules must be defined in separate files.

export memberexports a member from a fileimport { member } from "file"imports a specific member from “file.js” (this may sometimes look like destructuring, but it is actually special syntax for modules).import myMod from "file"imports the entire module from file- Modules API are static: Compiler will check that all references to modules and module members exists at compile time, if not it will throw an error.

- Contents in module files are treated as if they are enclosed in a scoped closure.

- Methods and properties exposed by modules are actual bindings to inner module definition (which means the value can be changed dynamically, and reflected when all references to the module property resolves).

- Modules are singleton, and will not be re-imported again.

- Circular Module Dependency is supported, since all module imports will be resolved and loaded first before any function calls are executed.

Direct Interaction with Module Loader

- The module loader is provided by the hosting environment of JavaScript Engine.

- Sometimes it may be necessary to directly interact with the module loader, to load external resources/modules or dynamically load non-JavaScript code.

- This will incur a performance penalty, so we should only consider this if it is truly necessary.

Execution

Hosting Environment and Event Loop

- The traditional hosting environment of the JavaScript engine is the web browser.

- Node.js is a server-side alternative, and there are other modern environments that may even be embedded systems.

- The JavaScript engine and the hosting environment interacts with the event loop.

- The engine executes functions that are on the loop, one-by-one on a single thread, (which is why many people refer to JavaScript as single threaded).

- At each tick, an event will be picked up from the loop and executed by the engine.

- The hosting environment may insert event into the loop upon completion of asynchronous operation.

- E.g.

setTimeoutinteracts with a timer provided by the hosting environment, and when time is up, the hosting environment will insert an event into the loop. The engine picks up this event and execute the callback function that was provided whensetTimeoutwas initially called.

Event Loop Concurrency

- Two task queues may be interleaving their tasks in the event loop, resulting in unexpected outcomes depending on their concurrency model, explained below:

Non-Interacting

- The two task queues do not affect each other in any way, therefore the true sequence of event execution by the engine does not matter.

- Cooperative model happens when each task queues limit the execution time of their events, allowing many other task queues to gain sufficient execution time on the event loop for the entire program to progress as a whole.

- This can happen by breaking the big tasks down into smaller tasks and inserting those tasks back into the loop.

Interacting

- The two task queues may be modifying the same variables within the same scope/context, or the outcome of the entire program execution depends on these shared variables.

- The outcome may be vastly different if the sequence of event execution changes, making the program non-deterministic.

- We can overcome this issue by simple coordination between two task queues to make sure certain critical events do not overlap.

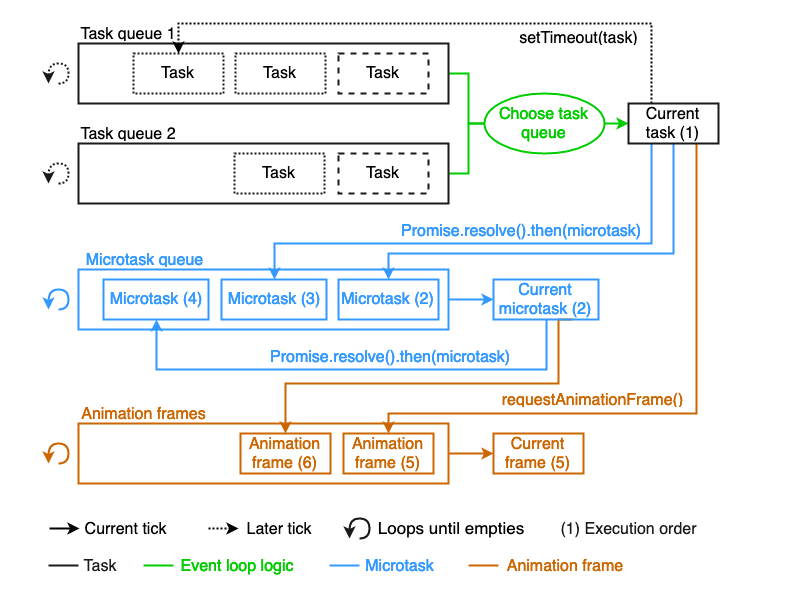

Tasks and Microtasks

![[image-event-loop-task-queue.png]]

Image sourced from RisingStack blog

- Each task will run to completion on each event loop tick

- The next task will only begin at the next tick.

- At the end of each task, the microtask queue will be processed until the queue empties.

- (

Promise.thenis the simplest way to schedule a microtask).

- (

- Rendering is handled by the main thread in the browser and therefore the render task needs to be scheduled as well.

- Rendering may take place between event loop ticks.

- The sequence of execution goes like this: task > microtasks > render

Important! Having this knowledge does not mean that we should use the scheduling of tasks and microtasks to enforce any kinds of event ordering!

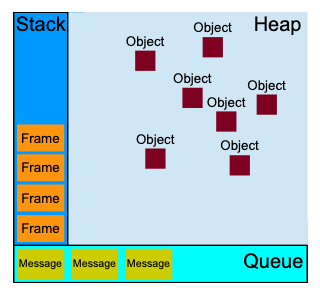

Runtime Model

![[image-javascript-runtime-model.png]]

Image sourced from MDN web docs

Garbage Collection

- There is no need to release memory explicitly.

- This will be handled by JavaScript Garbage Collector.

- A mark-and-sweep algorithm is used to overcome the limitation of circular reference (this algorithm is able to identify a set of circular references that are isolated and can no longer be referenced, therefore is GC-eligible).

Performance Optimisation

- Web Worker/Shared Worker is a feature of the browser host environment to allow JavaScript program to run on separate threads (access it through browser API).

- Data can be transferred by simple copying or by using Transferable Objects.

- Main advantage is to prevent intensive computation or interaction with external resources from slowing down the main thread.

- It also allows your program running on multiple tabs to share a set of common workers.

- SIMD optimisation (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) requires API to allow JavaScript program to tap on modern CPU’s SIMD processing capabilities, that speeds up vector calculations.

- asm.js is a subset of JavaScript language.

- We use it by compiling our code to meet asm.js specs first, then allow environments that support asm.js to run it.

- Optimisation is largely derived from static typing and coercion, as well as reserved heap for modules to avoid expensive memory operations during runtime.

Performance Benchmarking

- There is little benefit to writing your own benchmarking framework/utility. Use a tool like benchmark.js.

- jsPerf is a site that uses benchmark.js to create an open platform for testing.

- Certain performance difference hardly matter. (Average human cannot perceive anything faster than 100ms).

- Engine optimisation may provide unrealistic performance result due to detection of static values, which cannot replicate actual environment.

- No need to be overly worried about micro-performance optimisation in our code, as the constant browser engine improvements will likely make a lot of these micro adjustments obsolete.

- Focus manual effort on optimising the critical path.

The Golang post about performance is relevant for JS as well.

- journal: [[202504272216-pub-efficient-go]]

- web: benchmarking

Tail Call Optimisation

- ES6 specification requires engine to implement Tail Call Optimisation.

- If a recursive function call occurs at the end of a function definition, there is no need to allocate a new stack frame, as the existing frame can be reused to run the next recursive function execution.

- This optimisation speeds up execution and reduces memory usage.