Clean Architecture

Work in progress.

Clean Architecture

Clean Architecture A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design - Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob), 2018

There are many things to look out for when reviewing a Merge Request/Pull Request, but none as important as the architecture and design of the code. By setting up proper practices and automation, we can ensure that requests are small, single purpose, comes with unit tests and passes benchmark code quality check, but only a human reviewer can verify if the architecture of the code is clean and in alignment with the initial design the team has set out to achieve. There are no tools to help the reviewer, besides having a good knowledge of Clean Architecture.

… the rules of software architecture are independent of every other variable. … those timeless, changeless, rules

Robert C. Martin

Introduction

The goal of software architecture is to minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system.

A software system however, brings two value to the business stakeholders.

- Functional value, the system provides features to meet business requirements.

- Architectural value, the system is able to adapt quickly and easily to new business requirements.

Very often, urgency of delivering functional features outweigh the importance of creating good software architecture. It is the responsibility of the development team to advocate and assert the importance of architecture over the urgency of features.

The Building Blocks

A piece of software is made up of building blocks, each building block has its own good practice and principles that we should seek to learn and follow.

Programming Paradigm

The book introduced the three paradigms in sequence, to show that each paradigm incrementally removes capabilities from the programmer. Each paradigm imposes extra discipline and advocates what negative practice the programmer should be avoiding.

The book also stated that there were no new paradigms discovered after year 1968, suggesting that this is an exhaustive list.

Structured Programming

Structured programming imposes discipline on direct transfer of control

A good example to see this paradigm in action is through the game, Human Resource Machine.

In this game, there are no if/then/else or do/while control structures, and players will need to implement such structures on their own using actions similar to goto. Often to produce the most optimized solution in the game, players will need to abuse the goto capability and create something that would be considered dirty code.

However, as the book has pointed out, such code cannot be decomposed recursively into smaller units, therefore prevents the use of divide-and-conquer strategy and impose a challenge for producing reasonable proofs of correctness. If the program is not provable, then no matter how many tests we perform, we cannot deem that it is correct.

Modern day programming language already removed unrestrained goto support, and control structures like if/then/else and do/while are provided by default, hence we are already influenced to do structured programming without even realising, and we all adhere to certain discipline on direct transfer of control.

Object-Oriented Programming

Object-oriented programming imposes discipline on indirect transfer of control

The three defining traits of OOP:

- Encapsulation = grouping data and functions into a cohesive set, outside of the group only certain functions are known, while data is hidden.

- Inheritance = re-declaring of a group of variables and functions, within an enclosing scope, in another group that is a pure superset of the initial group.

- Polymorphism = the use of pointers to functions to call different functions depending on the pointers that were declared initially.

The book pointed out that encapsulation and inheritance can already be achieved through the C language, but polymorphism support in OOP languages is the trait that truly helps us impose discipline on indirect transfer of control as programmers do not need to explicitly set pointers to functions and to remember and implement conventions manually which is dangerously error-prone.

Polymorphism also enabled the widespread adoption of plugin architecture, through dependency inversion. We know that program control flows from higher-level functions to lower-level functions, but instead of having higher-level code also directly depend on lower-level code, we can invert the dependency, by making higher-level code depend on an interface. Polymorphism then allows the lower-level code implementation to be plug-able to that interface.

Absolute control over the direction of all source code dependencies, not constrained to align with flow of program control.

Functional Programming

Function programming imposes discipline upon assignment

Variables in functional languages are immutable. The impact on our architecture is the avoidance of race conditions, deadlock conditions, and concurrent update problems, since these issues are all created by mutable variables. Therefore, we impose discipline upon variable assignment in our program.

To practically incorporate the immutability into our architecture requires segregation of mutable components from immutable components. Mutable components cannot be fully avoided due to interaction of the system with external services. However, with sufficient resources, event sourcing can be considered to only store immutable transactions, and compute state from those transactions when required.

Design Principles - SOLID

SOLID principles apply to cohesive groupings of functions and data structures, and these grouping should be interconnected. In OO languages, it is usually the class, but it does not mean that SOLID principles only applies to classes. It is equally relevant in JavaScript.

The goal of SOLID principles is to create module level structures in a software that are

- adaptable to changes

- easy to understand

- reusable components

Single Responsibility Principle

Module should be responsible to one single actor

The meaning of SRP is not that a module should only do one thing. That is a misconception. SRP means that the functions and data structures in a module are cohesive enough, to only be changed when it’s only actor requires the module to make a change. If two actors cause a single module to change, that module has violated SRP

Common pattern to tackle the problem in a class with too many responsibilities is to first reduce the scope of the class, then move the other functions that has been eliminated into separate Single Responsibility classes. Access to the original class should be swapped with a Facade class, that interacts with this group of now decoupled classes.

Open-Closed Principle

A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification

What it means is an artifact should be extensible without any modification. And this can be done by heavy use of interfaces.

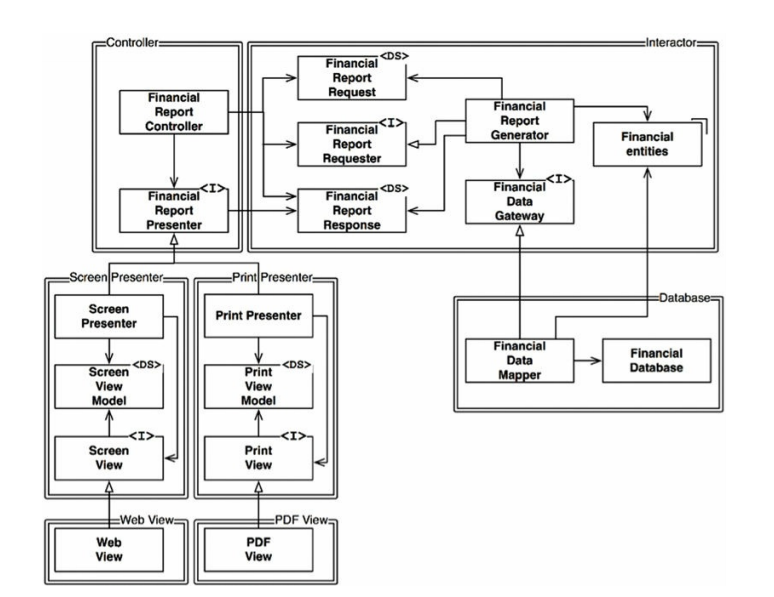

This high-level onion abstraction of our software can be created using classes and components with uni-directional relationships.

- double-line boxes represents components

- single-line boxes represents classes

<I>annotates an interface<DS>annotates data structure- anchor at the top right corner of a box annotates a domain model

- open arrowheads represent using relationship

- closed arrowheads represent implements or inherits relationships

Notice that components that maps to the inner layer of the onion architecture are protected from changes in the outer layers of the onion.

Liskov Substitution Principle

essentially polymorphism. S qualifies as a subtype of T, if objects of S can seamlessly replace all objects of T, inside a program defined in terms of T.

Classes can inherit from parent classes, and seamlessly replace objects of parent class in the program. From a broader, architectural perspective, we again make heavy use of interfaces between components and classes to uphold this good principle.

Special Note - we can achieve the same result using composition (instead of a class inheriting or implementing an interface, we have an object that delegates to members that conform to the interface, and this object becomes an adapter/intermediary layer) when working with JavaScript. The good principle will still be conserved as this is just an implementation detail. And as the Gang of Four has said, prefer composition instead of inheritance when possible, as it often simplifies your code.

Interface Segregation Principle

clients of an interface should not be forced to implement more methods than necessary

Violating the principle just means that the interface itself can be further broken down into decoupled interfaces. This principle protects us from unnecessary changes to components simply because its dependency violated this principle, and has an additional baggage that needs to be changed, which is entirely unrelated to the component’s main function or behavior.

Dependency Injection Principle

source code should depend on abstractions, and avoid volatile concretions

Some golden rules:

- Don’t refer to volatile concrete classes

- Don’t derive from volatile concrete classes

- Don’t override concrete functions

The Abstract Factory pattern showcases this principle, as the client of abstract factory only works with the interface of a factory, and interfaces of the entire family of objects created by the factory. At a higher level above the client, the concrete factory is injected into the client, therefore the client’s source code will only ever work with abstractions, no concretions.

Special Note - I was confused between Abstract Factory pattern and Factory Method patterns and did a quick search. Abstract Factory is a pattern used to produce a family of related objects from a factory, in contrast the Factory Method is only responsible for returning one object. Both patterns essentially defer the actual object creation to another layer, away from the client.

DIP violation cannot be entirely removed as we ultimately need to handle concrete classes. Most systems contain the handling of concrete components in a main function, which would instantiate all necessary concrete implementations depending on configuration, place these objects in a global variable, accessible to the entire application, and other parts of the source codes will only be dealing with these global variables through abstract interfaces.

Component Principles

Applying the above SOLID principles makes good modules, and now we need good principles to compose those modules together to form components.

What is a Component

Some concrete examples are .jar files in Java, gem files in Ruby, DLLs in .NET, and my guess are NPM packages in JavaScript. Regardless of language, good components are always independently deploy-able and develop-able.

Component Cohesion Principles

These principles deal with the appropriate classes to include in a component.

Reuse/Release Equivalence Principle

The granule of reuse is the granule of release

Components should have proper release versioning and documentation to allow users of the component to easily reuse them in their own applications. This can be facilitated by module management tools and package repositories.

But to have proper release, all classes and modules inside a component must be cohesive enough to be releasable together. In other words, the user of this component do not need to worry about the internals of the component being not up to date, and only need to perceive the component as one single, granular unit.

By extension, when organizing components/features within our own application, if we eventually intend to release those as individual packages, we should also take REP into consideration.

Common Closure Principle

A component should be a group of classes and modules that change for the same reasons, at the same time.

This is SRP from SOLID principles, but applied to the component level. Maintainability is usually more important than reusability. If we require a change in the application, we want to ideally limit it to a component, rather than having to distribute the change across many components.

Common Reuse Principle

Don’t force users of a component to depend on things they don’t need

This is similar to ISP in SOLID principles but applied to the component level. The consumer of a component ideally uses all classes and modules in the component (component internals are tightly cohesive), if not this dependency will carry baggages of unused classes and modules, and any changes to those unused internals will also propagate changes to the consumer for no good reasons.

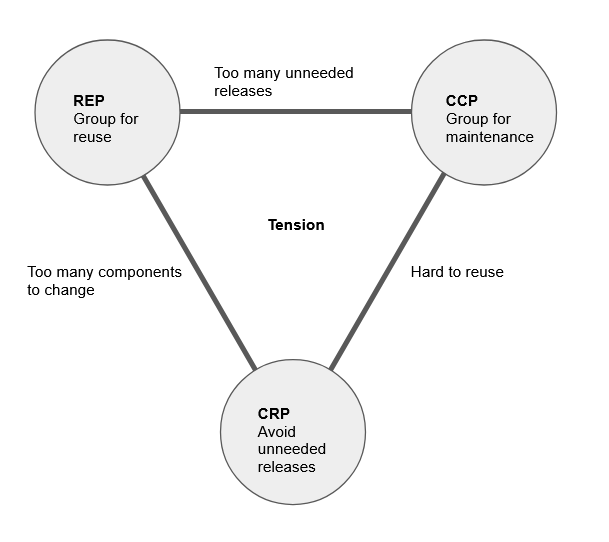

Tension Triangle

When we evaluate a component, we will find that it lands somewhere within the triangular space. Edges of the triangle describes the cost of abandoning the principle on the opposite vertex. A good architect will evaluate the tradeoffs and seek to craft the component at a suitable position in the triangle, but make it appropriate and relevant to the current state of the project.

Early development of a project will likely focus more on CCP to improve develop-ability and collaboration in the team. However as project matures, focus will be shifted to the left of the triangle as there will be more external consumer of the components, and the team will need to be concern over release management.

Component Coupling Principles

The above three principles deals with the internals of a component, the next three principles deal with the interaction between components.

Acyclic Dependencies Principle

Allow no cycles in the component dependency graph

Components in an application can be mapped on to a dependency graph. Having cycles in a graph means that there will be a subset of all components that are so tightly coupled that they cannot be easily build and release without stepping all over each other’s work. This subset of components behave as one large component block in the system.

Having a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) on the other hand means that each component only need to be concerned with maintaining their own releases, and the consumers of those components can decide which release version to consume. This allows easier and faster building of the application, and determines the order of component build.

Cycles can be broken by applying Dependency Inversion Principle, using interfaces to separate the dependency of two component, and extract out common elements of the two components into a new concrete component that implement the interfaces. This new concrete component becomes a sink that absorbs the flow of dependency direction, breaking the cycle.

It is not realistic to create the component dependency graph from top down since day one. We should gradually evolve our components as the project progresses and mature.

Stable Dependencies Principle

Depend in the direction of stability

Stability measures the amount of work required to make a change. A component is highly stable if a lot of other components depend on it, but itself has no dependency on others. A component is highly unstable if it only depends on other component, but no others every depend on it. It is obvious that updating a stable component will cause a lot of repercussion than an unstable component.

Special Note - Stability is just a measure, and it does not indicate whether more stability is good or bad. The system needs both stable and unstable components, the key is to arrange the dependency graph of the system, such that components are less likely to change are stable, and components that are volatile are unstable.

Formula for calculating positional stability of a component:

- Fan-in: number of classes outside of this component that depends on classes inside this component (i.e. number of import statements importing classes/modules from this component)

- Fan-out: number of classes inside this component that depends on classes from other components (i.e. number of import statements this component is using)

- Instability: I = Fan-out / (Fan-out + Fan-in)

If a component has no Fan-in, which means nothing depends on this component, it will have I = 1, meaning it is maximally unstable. If a component has no Fan-out, which means it does not depend on anything, it will have I = 0, meaning it is maximally stable.

If a component, named A, is expected to be stable but is depending on another highly volatile component, B, we have a design problem and we will run into the unpleasant situations of having to update A unnecessarily when B changes. The solution to this is again the use of Dependency Inversion, to make both components depend on an interface. Therefore A which depends on the interface remains stable. B is unstable, but it only depends on the interface and is free to change. The interface itself do not depend on anything, so it is maximally stable.

Stable Abstraction Principle

A component should be as abstract as it is stable

Abstractions allows a stable component to still be flexible to changes in future without causing pain to its dependents.

Formula for measuring Abstractness:

- Nc: number of classes in a component

- Na: number of abstract classes/interfaces in a component

- Abstractness: A = Na / Nc

A = 0 means there are no abstract classes or interfaces, A = 1 means that there are only abstract classes.

Looking at both Instability I and Abstractness A, we can identify the characteristics of a component and its impact to our system.

- A highly stable component with no abstractions (I = 0, A = 0) typically causes a world of hurt as it is extremely difficult to change. An example would be database schema that sits between the database and an OO application. Database schema is highly volatile in the early stage of the project and we simply don’t have a good way to provide abstraction. If the component is non-volatile however, such as a library like

momentJS, it is less of a problem as we are not expecting much changes. - A highly abstract and unstable component (I = 1, A = 1) is typically useless, as no other components are using it. Usually these are legacy zombie code.

So it seems like the line that connects (I = 0, A = 1) and (I = 1, A = 0) is where we should strive be place our component. (The book calls this line the Main Sequence). To put it into words, an increasingly stable component should be increasingly abstract.

These metrics, I and A, and the distance between the current component’s metric from the Main Sequence line can be collected over several releases to perform statistical analysis and process control, to monitor and measure design changes in our software.

Architecture

Software architects pull back from code to focus on higher-level issues. This is a MISCONCEPTION. Software architects are programmers, the best in the team. They cannot do their jobs properly if they are not experiencing the same problems they are creating for the rest of the team.

Architecture Objectives

Software architects aim to create the shape of a software system, which is described by:

- how the system is divided into components

- how those components are arranged

- how those components communicate with each other

And the main objective of any architecture should be to facilitate development, deployment, maintenance and use case + operation. The general strategy behind that facilitation is to leave as many options open as possible, for as long as possible.

(Even though use case + operation is one of the main objective, very often good architecture has little bearing on whether the system works. We have all seen terrible architecture that works. They are terrible because they have neglected all other objectives besides their use case + operation. And very often, we end up with terrible architecture because we locked ourselves out from other possible options and limited the flexibility of our system, because we think that in order to meet timelines and ship our release fast, we need to take shortcuts in our design.)

Facilitate Development

A well-defined architecture with reliably stable interfaces facilitates development for most team structures. And systems that are more develop-able have long shelf life.

Failure to craft out a good design upfront either results in a monolithic system run by a single team of engineers, or a per-component-per-team architecture in a multi-teams environment, plagued with collaboration and communication issues.

Facilitate Deployment

The higher the cost of deployment, the less useful the system is.

A classic example is the decision to use micro-service architecture early as it has well defined component boundaries, making development easy. However, the teams eventually find it a nightmare to deploy the architecture due to the daunting task of configuring connections between services and the tricky dependency of their deployment sequence.

Facilitate Operation

Operational needs of the architecture can often be solved by using more and better hardware resources, and it is often easier to make a bad architecture work, than to facilitate development, deployment and maintenance.

However, good architecture should strive to reveal the operation by elevating the use cases, features, and required behaviors of the system as first-class entities, so that it is apparent to all engineers of the system. This also benefits development and maintenance.

Facilitate Maintenance

Maintenance is the most costly aspect, due to the vast amount of manpower it consumes to dig through existing code, make changes for new features, and inadvertently causing more bugs and defects.

Good architecture creates stable interfaces of isolated components, making it easier to update the system with new features, and limit the risk of major breakage.

Defer Decisions As Much As Possible

All software system can be decomposed to two major elements:

- Policy = embodies all the business rules and procedures

- Details = interacts with external dependencies, devices, and users

Ideally, the architecture of our system should recognize policy as the most essential element, and that details are irrelevant to policy since they should never influence our software behavior. So decisions regarding details should be delayed and deferred as much as possible until the last moment.

This lazy decision making buys us more time and information to make a better implementation decision, and retains the flexibility for us to experiment with different technology while preserving the core system behavior (a nod to Domain Driven Design and Onion Layered Architecture).

Achieving Independence

All things mentioned above are easier said than done in the real world. As a system moves through its life cycle, team structure of engineers, user requirements, system behavior and use cases change. However, some good principles of architecture are eternal, and following these principles can help us make the system easy to change.

Decoupling Layers

A system can be decoupled by horizontal layers, as an example just to name a few:

- the UI

- the application-specific business rules (e.g. validation of input fields)

- the application-independent business rules (e.g. compute interest on account balance)

- the persistence (e.g. database)

Decoupling Use Cases

Use cases are narrow vertical slices that cut through the horizontal layers of the system, and between use cases they change at different rates and for different reasons. Such decoupling that cut through the horizontal layers allows each use cases to use a different aspect of e.g. UI and the database, so that adding new use cases will not affect existing UI and database aspects.

Decoupling Mode

Operational needs may different for different use cases. For e.g. some may need to run at large scale, some may need to be strongly consistent. We may need to create separate services to meet the different operation modes, and communicate over the network.

This can be done at a few levels:

- Source code level decoupling = they are only logically separated, but it is still a monolithic structure. The best we can achieve is perhaps to avoid recompiling other components, by properly structuring the dependencies of decoupled source code. All components still needs to be deployed together, and they execute as a single executable loaded in computer memory.

- Deployment level decoupling = components are decoupled into independently deployable units, like JAR files, GEM files, DLLs, or NPM packages. They may still be executing in a single shared memory.

- Service level decoupling = components are entirely decoupled (source, binary, and deployment) and only communicates over network.

Uncle Bob recommends delaying the decision to the last moment. Build our system with a good architecture approach that protects majority of our source code from such decoupling of mode. We can start with monolith, only move to services when the requirements arise, and still have the flexibility to slide back to monolith when system life cycle further evolves.

Special Note: Duplication

Do not be tempted to commit the sin of knee-jerk elimination of duplication. There are two kinds of duplication:

- True duplication = in which every change in one instance necessitates the same changes to every other instance.

- Accidental duplication = it so happens that right now, the code in two instances are exactly the same, but over time they may evolve along a different path.

My guess is, true duplication would be the copy-pasting of code to create the same objects and models in frontend and backend code, which will force you to keep the code always in sync. These are the duplication we want to eliminate by unifying the code either through code-gen from API contracts, or importing of packages/SDKs.

On the other hand, accidental duplications are two UI screens looking very similar, but to operate on different use cases. Over time these two use cases are expected to evolve along different paths, and pre-mature unification of duplicated screens are going to pose a challenge to future development.

Drawing Boundaries

In this chapter, Uncle Bob shares a personal anecdote about delaying implementation decisions to the last moment, and developed a fully working version of FitNesse for over a year without a database. It was a nice story that turns a lot of software design tutorials we know on its head.

The key point here is to partition the system into components, where business logic components are at the core, and other components such as IO, databases, frameworks, are simply plugins to the architecture, which depends on the core, but are free to change without interfering with the core. This is done through the application of Dependency Inversion Principle and Stable Abstractions Principle.

In general the “level” that a component resides depends on its distance from the inputs and outputs of the software. Therefore the core logic is the furthest from the inputs and outputs, and is at the highest level, whereas IO is at a low level with direct interaction with the inputs. Low level components should depend on high level components, and does not necessary align with the direction of control flow or data flow.

Business Rules

At the core, we identify a set of Critical Business Rules that work on Critical Business Data. They are critical because they are the main value proposition of our business. Even without software, if we are using humans to carry out the rules and operate on the data, it is still a profitable business.

Entities

Entity objects encapsulate critical business rules as methods that operates on critical business data.

It is a no-nonsense, pure-business, object, decoupled from everything else in the system.

Use Cases

Use case is a description of a way that an automated system is used. It specifies:

- input to be provided to the use case

- output to be expected from the use case

- processing steps needed to produce the output

It describes application-specific business rules as opposed to critical business rules within entities. Use cases specify how and when critical business rules within entities are invoked.

Other important notes:

- Use cases are lower level compared to entities, therefore dependencies point towards entities (i.e. entities do not know what use cases are using them)

- Use cases do not deal with UI, IO, or frameworks. It still deals in the core of the software, but is application-specific business rules.

- Use cases accepts simple request data structures as input, and returns simple response data structures as output. These are also independent of devices and technology. They are also entirely decoupled from entities even though they may contain the exact same data!

Screaming Architecture

The architecture should scream the use case and the purpose of the system. It should be apparent to the engineers joining the team just by reading the code. And the new members have the freedom to adopt new frameworks, libraries and technologies as plugin to the core system easily.

Uncle Bob emphasize in this chapter to develop a strategy that prevents any specific framework that we may adopt from taking over our architecture, and preserve our use cases as our core concerns.

Personal reflection: I think this applies to modern frontend applications that make heavy use of frameworks, e.g. a React application. Just because we have a framework, and endless online tutorials teaching us how to build React components, it should not prevent us from keeping our business logic clean and decoupled, and use case driven.

The Clean Architecture

The principles behind this concentric image has been discussed in great details throughout the book. The layers are expected to evolve at different rate, with the inner most layer being least likely to change over time.

Interface Adapter

This is the layer responsible for converting data most convenient for use cases and entities, to the format most convenient for external agency like the database or the UI. For e.g., it consists of the entire MVC architecture of some UI framework, or any persistence framework that works with certain database.

Frameworks and Drivers

Generally we don’t write much code in this layer besides the glue code to communicate with the next layer inside the circle, since these implementation details will be provided by the technology we choose to use.

Crossing Boundaries

Personal reflection: This is perhaps the hardest concept for me, as I struggled for a long time to understand what it truly means for dependency to oppose the direction of control flow.

The lower right diagram shows the flow of control in the layers, it is fine for controller to depend on the inner use case layer. However, after use case processing, in order to pass the data back to the presenter, the use case MUST NOT have a dependency on the presenter. So we mitigate this by depending on an interface instead, and use dependency injection to inject the actual presenter. This ensures that dependency flows in the opposite direction of control.

Data Across Boundaries

Data that are passed between layers should be simple structures or DTO. NEVER be tempted to pass raw database records or JSON requests into inner layers, violating the dependency rule.

Humble Objects Pattern

The idea is simple, split a software behavior that is hard to test into two modules:

- One is a humble module, that contains all the hard-to-test behavior stripped down too their barest essence. It is dumb, with almost no logic.

- Another module will contain all the testable behaviors stripped from the first humble object.

For e.g., a View is a humble object. We do not intend to test the view since it is difficult, so we keep the View as dumb as possible. The View renders what ever is provided by a Presenter (that is why the View is humble). The Presenter contains all the testable behavior, to transform all the given input into a simple data structure expected by the View. This allows us to easily test the Presenter by setting our inputs and asserting the outputs.

For e.g., a database gateway is a humble object, using SQL queries directly depending on the technology we choose to use. The use case interactors depend on gateway interfaces, which allows us to test the interactors easily but have flexibility to mock or stub our gateway implementations. By this logic, ORMs belong to gateway layer, and are therefore humble objects. (Note, Uncle Bob seems to hate the term ORM, as calling data structures “objects” are misleading in the OOP paradigm. He prefers to call them “data mappers” instead of ORM).

For e.g., service listeners for external devices or services, are also humble objects.

Partial Boundaries

Three approaches to having placeholder boundaries, which provides flexibility to creating full-fledged boundaries as architecture evolves, but do not incur upfront overhead.

- Define all the boundaries, but keep the code within one component. It will still require development effort, but do not have any release management overhead.

- Strategy Pattern, to set up a one dimensional boundary using an interface, without a reciprocal boundary interface (Note: I do not understand what Uncle Bob is saying…)

- Facade Pattern, to allow clients to depend on a Facade class that accesses other services.

Implementing Boundaries

We are always balancing between the YAGNI principle to avoid building costly boundaries that we will never use, and the risk of under-engineering and breakage when we eventually do want to add in architectural boundaries.

Our goal as architects is to implement the boundaries right at the inflection point where the cost of implementing becomes less than the cost of ignoring.

The Main Component

The main component should be the dirtiest low-level module in our architecture, to set up initial conditions and configurations, gather all outside resources before handing over control to higher level components.

However, we should also think of it as a plugin, meaning we can potentially have many main components plugging into our architecture, perhaps one for Dev, one for Prod, one for each country or each tenant of our software etc.

Services

There are two fallacies related to services.

- Services are no more rigorous, or formal, or better defined than traditional function interfaces. Services are essentially function calls, over the network instead of within a process. Tightly coupled services still change in lock step. Therefore, it is important to remember that microservices, SOA, are not architecture, in the same sense that this book has been discussing, but rather deployment/operation modes of certain components in our architecture.

- Services do not really offer the benefit of independent development and deployment, since tight coupling and deployment dependencies can still occur. Also, any new features with cross cutting concerns affects all services, so there are no benefit to deployment or development in using services in this scenario.

Personal reflection: It is surprise to hear Uncle Bob point out that services are not architecturally significant elements. Architecture are solely defined by component boundaries within the system, and their dependency rule, regardless of the physical mechanism by which the program communicates and executes (which are services!)

A service may house a single architectural component, or several components with clear architectural boundaries.

In conclusion, adopting micro-services/SOA do not equate to good architecture. Good architecture requires the application of good design principles.

Test Boundary

Tests are part of our system. It is a component that sits on the most outer layer. No system code depends on our test, making it a most ideal plugin component of our architecture.

Fragile Test Problem

This problem occurs when we realise that a small code change breaks hundreds of tests, which inevitably makes our system rigid to changes. Therefore, the golden rule to software design, whether for tests or for other components, is to NOT DEPEND ON VOLATILE THINGS.

Personal reflection: It is funny to know that Uncle Bob thinks GUIs are volatile, and therefore tests that depends on GUI (e.g. mimicking user click actions on login pages) must be fragile. Makes me wonder what frontend engineers think about this comment and what is their philosophy to testing.

The Testing API

A set of API, that is the superset of the suite of interactors and interface adapters that are used by the UI, that allow our tests to call. This API have superpowers to bypass expensive resource initializations, external conditions, security constraints, and can immediately put our system into a particular test state. Having this API helps us decouple the structure of our test from the structure of our application.

If we have deep structural coupling, creating a test class for every single production class, and a set of test methods for every production method, the overhead from making small code changes will be overwhelming. The testing API will help hide the structure of the application, allowing our tests to assert for very specific outputs, but allow our production code to evolve and become more generic and flexible.

Note: if security is a concern, this testing API should be deployed independently as yet another plug-able component, and never deployed in production.

Details

The database the web, and the rest of the frameworks are details. They should not affect our core architecture since dependencies point inwards.

- Database technology can change. We may need to adopt new database technologies very rapidly, and a good architecture will allow us to do so without changing the core business logic.

- The web is merely a detail that determines how the server and the client communicates. This may change as our project evolve. We may need native support on mobile devices. Again, a good architecture will allow those transitions without affecting the core logic.

- Frameworks are dangerous, because the framework author and other advocates will encourage you to allow the framework to dictate your architecture. It works for them, because they created it to suit their specific goals, but most of the time you will not find a perfect match for your own project. And your project will evolve over time, and there is no guarantee that the framework will continue to grow in the same trajectory. Framework should be a plugin to your own architecture.

Packaging by Layer

Traditional horizontal packaging of layered architecture works as a good starting point for most architecture, but will not be able to keep up with complexity well. Each layer will grow into a huge repository by itself, with implementation of features cutting through all layers spread across these packages.

Packaging by Feature

This is vertical packaging. Within each package contains code that cuts across all layers. This approach is also sub-optimal as it is difficult to keep up with complexity.

Package by Ports and Adaptors

This approach packages the domain, and keep it isolated from external details, which can be in their separate packages since they are merely adaptors that plugin to our domain. The issue with this approach is the lack of control, as adaptors can directly communicate with each other, potentially modifying data through persistence layer.

Package by Component

This approach takes the above Ports and Adaptor approach one step further, by splitting the domain up into components. Components group similar concepts into a single unit, so that we only expose a single clean interface for each concept to the adaptors that are plugging into our architecture. The persistence layer will be part of our component, so that it will not be exposed to other adaptors outside of the components.

Conclusion

The conclusion in this section has got to be the worst advice, because it is just a high level reminder of the challenges you will face.

When planning your implementation strategy, consider:

- how to map design into a desired code structure, and how to organize that code.

- which decoupling mode to apply during runtime and compile-time.

- leave options open where applicable but be pragmatic.

- size of your team, their skill level, the complexity of the plan, budget and time constraint, before making a decision.

- tools like compiler features, to help enforce the chosen architectural style.